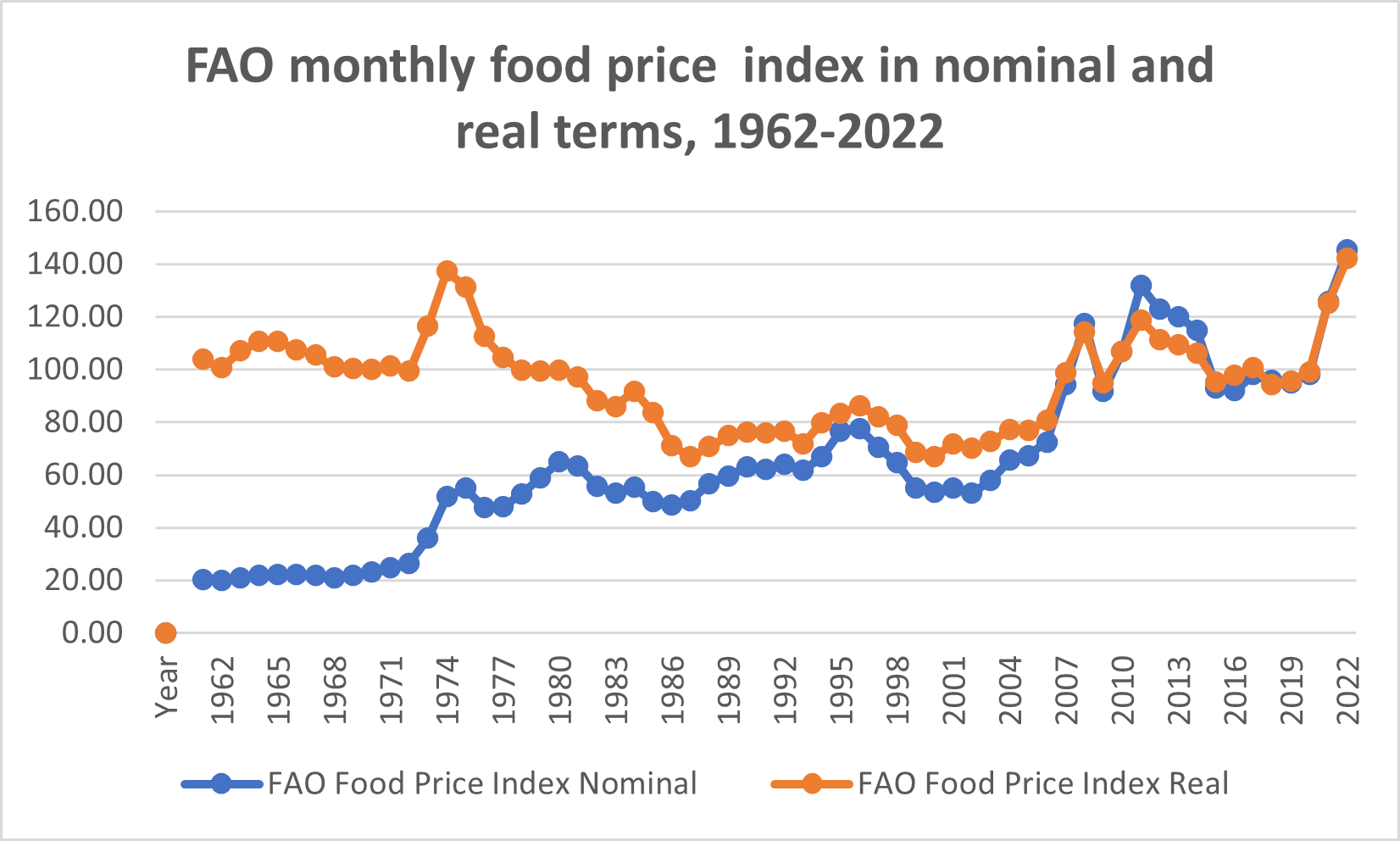

The FAO Food Price Index indicates that global food prices hit an all-time high in March 2022.

The index, which is comprised of the average of five commodity group price indices weighted by the average export shares of each of the groups, reached 159.3 points in March, up by 12.6% from February when it had already hit the highest level since 1900 (See Figure 1).

The Food Price Index is intended to capture and compare the monthly outcome of changes in a variety of food commodities, including vegetable oils, cereals, dairy, meat, and sugar. The agricultural commodity index indicates that maize and wheat prices are 48% and 60% higher respectively, compared to January 2021, while rice prices are about 17% lower. Taking comparative Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita levels into account, the UN estimates that food prices in Sub-Saharan Africa are now 30-40% higher than in the rest of the world. Thus, it’s evident that the global food crisis is likely to threaten the livelihoods of millions of people in Africa, who are already extremely vulnerable due to high rates of poverty, hunger, malnutrition, and food dependency. For example, according to the World Food Programme, currently, 26 million people do not have sufficient food in the Sahel and West Africa region while additional 2 million people in the Central Africa Republic are acutely food insecure. Correspondingly, about 14 million were severely food insecure in the Horn of Africa as of March 2022. As economies recover from the Covid-19 crisis, higher food prices have contributed to a general increase in inflation. Compounding the looming food crisis, historical injustices, inequality, and wealth extraction have left generations of Africans impoverished and national economies in debt threatening the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030.

In light of the above, this is a good time to re-examine some important questions. Thus, this article seeks to unravel answers to questions arising from the rise in global food prices with a focus on Africa post-Covid-19. The first question is to what extent have the poor in Africa been affected by these global food price rises? Second what types of policies have been put in place to cushion the poor? Third, to what extent are the policies implemented in Africa targeted at the poor and how can they be improved?

Skyrocketing prices

According to Pope Francis, we are all accountable for world hunger. He notes that climate change and increase in conflict, as well as lack of investment in the agricultural sector and unequal distribution of earth’s products, are concerns that must not leave us indifferent or resigned. The catholic church understands the food crisis as a serious bottleneck to the human right to life and human dignity as it is a denial of the means to support that life and dignity-a dignity that is God-given. Strikingly, climate shocks, locust invasions, violence, and terrible economic circumstances preceding the Covid-19 pandemic were having a huge impact on agricultural food productivity and food availability in Africa. The prices of locally produced food have remained abnormally high in Africa, driven by a production deficit across the region. At the same time, the prices of imported food commodities in the region are at a record high, driven by increases in international markets, transport costs, and trade barriers. With the break of the Covid-19 pandemic, the already-vulnerable food systems were debilitated by the pandemic that cut short global food supply further pushing up the cost of food and resulting in rising cost of food access mostly in developing countries.

Even as the world struggles to readjust to the food market post-Covid 19, the ongoing Ukraine-Russia war continues to impact shockwaves in the food markets. Ukraine and Russia are the world's leading producers of sunflower oil, with the former accounting for 46% of total exports and the latter accounting for 23%. In 2020 African countries imported agricultural products worth US$ 4billion from Russia majorly wheat (90%) and sunflower oil (6%) while Ukraine exported US$ 2.9 billion worth of agricultural products in African countries accounting 48% (wheat), 31% (maize) and the rest included sunflower oil, barley, and soybeans. Egypt relies on Ukraine and Russia for 60% of its import. For developing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, a food price increase presents an onslaught to the peace and sustenance of livelihoods considering that food takes up a significant portion of the consumption basket. Consequently, a substantial proportion of households’ budgets are spent on food, necessitating actions to address rising food prices in Sub-Saharan Africa and their degenerative impacts on people’s welfare. In comparison to pre-pandemic forecasts, the World Bank anticipate that the combined crises of Ukraine-Rusia war and Covid-19 pandemic will result in an additional 75 million to 95 million people living in extreme poverty by 2022.

Food price increases can have a significant influence on lower-income households' living standards, as food accounts for the majority of their income. Families in Sub-Saharan Africa spend 40% of their income on food (the highest of any region), and the poorest are particularly reliant on cereals, which are growing increasingly expensive Even a little increase can force family members to make difficult choices. Consequently, regional instability could be exacerbated by the rising cost of living in African countries. Over time, the food price situation in Africa has attracted much interest from governmental and non-governmental organizations. Social unrest through demonstrations in African cities decrying the high cost of living is a common occurrence unlikely to end due to a lack of contingent measures to curb food prices going out of hand. For example, insurgencies in Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, and Nigeria have exacerbated food insecurity in West Africa, which is now experiencing its worst-ever food crisis.Likewise, in 2020 there were protests in Khartoum, Sudan against government’s decision to hike bread prices. Even though the situation may get dire since the spike in price is attributed to the recovery of global food demand from the global Covid-19 recession and the global supply chain disruptions. However, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) findings indicate that those Covid-19-related price variations may be short-lived due to stability in staple crops production in the 2021/2022 seasons as global demand weakens with economic recovery in China and other major economies.

In West Africa, food prices have risen by 20% to 30% in the last five years, owing to drought and conflict that have forced millions of people off their farms and slowed food production. Notably, the price of rice (+18%), sorghum (+24%), millet (+26%), and maize (+30%) have increased over the five years. The number of people in need of emergency food assistance as a result of food crises nearly quadrupled from 7 to 27 million between 2015 and 2022 in the same region. In Senegal for example, the economic sanctions against the neighbouring country Mali by the West African regional bloc Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) over a military coup have increased the price of beef in Senegal since Malian livestock can no longer be sold across the border. A trade embargo and the freezing of Mali's assets at the Central Bank of West African States are among the diplomatic, trade, and financial sanctions that were imposed. In Nigeria, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) which measures inflation increased to 15.92% year-on-year in March 2022 compared to 18.17 % in March 2021.

The Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development of the Republic of Uganda in a press statement in March noted that the price of essential goods and services such as cooking oil had drastically risen. Cooking oil registered the highest rise in price by 21% between December 2021 and February 2022 and a 77.6% rise in the past year. Similarly, in Zambia, an analysis by Zambian Business Times revealed that prices of meat shot up per kilogram with fillet and rump steak posting an increase in 25% between February 2021 and February 2022. In February, angry Kenyans took to social media to express their dissatisfaction with the country’s high cost of living which has been exacerbated by a rise in the cost of basic goods such as food, power, and fuel. They used the hashtag #lowerfoodprices to criticize the government for failing to control the rise in the price of basic commodities, which they claim has made living miserable. Fuel prices in Kenya increased for the first time in five months, causing commodity prices to rise as well. In addition, the cost of cooking gas has increased by 48%. As this happens, households’ allocation for food diminishes due to the burden on the overall cost of living, implying that the quantity and quality of food reaching the table is affected. In Sudan, there has been a surge in the number of people displaced due to conflicts that have eroded their livelihoods, damaged farms, and triggered widespread unemployment. Further, the depreciation of the Sudanese Pound (SDG) in addition to rising food and transportation has made it more difficult for families to put food on the table. In South Africa, Pietermaritzburg Economic Justice & Dignity Group (PMBEJD), which monitors the prices of food typically bought by lower-income families revealed that the there was a 10.6% year-on-year increase in the prices of 33 out of 44 basic foods in March 2022.

Policy Responses so Far

The current food price crisis, which has impacted thousands of households across the developing world, has once again highlighted the critical need for governments to strengthen their safety net mechanism to guarantee that rising food prices do not lead to an increase in poverty rates. More effective and coordinated action is required to assist the most vulnerable populations in dealing with the drastic and immediate increases in their food bills, as well as to assist farmers in meeting the rising demand for agricultural products. This unprecedented food crisis in Africa also provides an opportunity to address the root causes of food insecurity in the region by developing food and agricultural systems that are less reliant on external shocks, as well as more productive and efficient local agriculture, with a focus on the consumption of local food products.

Many countries are taking steps to mitigate the effects of rising prices on their populations. Algeria banned exports of all consumer products it imports including sugar, pasta, oil, semolina, and all wheat derivatives. In February 2022, the government of Burkina Faso took measures to safeguard domestic food supplies and contain upward pressure on the cereal prices including banning exports of millet, maize, and sorghum. In Nigeria, President Muhammadu Buhari recently commissioned a $2.5 billion urea and ammonia fertilizer plant to enable farmers to meet their agricultural production targets and access fertilizer which has been reduced significantly by the ongoing Ukraine-Russia war, threatening the global food supply chain. In South Africa, some activists groups such as Fairplay Movement have petitioned the parliament to remove a 15% value-added tax (VAT) from most chicken products as chicken is South Africa’s most popular meat protein source and the food product consumed by low-income households, thus zero-rating chicken is likely to target the poor, who are most affected by food price crises. In Uganda, the government is implementing a bottom-up economic model touted Parish Development model which aims to lift 17.5 million Ugandans out of poverty through total transformation of the subsistence households into the money economy and build capacity to withstand shocks such as price hikes.

Where do we move from here?

Food as a human right has long been a priority for food justice activists. Several international declarations, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the Preamble to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, have stated that food is a basic human right and is linked to the goal of eradicating poverty and hunger. Giving food producers a voice, recognizing the services they bring to communities, and altering regulations so that they can be better incorporated into food systems are all part of food justice. Experts are urging a rethinking of how we produce and distribute food so that everyone can have access to high-quality food.

Subsequently, building from the lessons learnt during the 2008 food crisis and the current hiking global food prices, several pathways can work toward stemming the rising food prices and their devastating effects on the households’ food access. The World Bank’s free flow of food recommendation can be instrumental in resolving artificial food shortages emanating from export bans by keeping food flows open. The idea of regional integration could be a good way to facilitate this World Bank recommendation. For instance, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) have been on the frontline in achieving food security among the member countries. The East African Community (EAC) has continued to attract more members to integrate, with the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) been the most recent and increasing the tally to six members. This implies the market for the availability of goods across the region and also facilitates food flows.

African governments must place a greater emphasis on safeguarding domestic producers' and suppliers' economic and social interests by promoting the national, regional and continental level structures and policies. They facilitate trade, but protecting the most vulnerable is a social responsibility that should be prioritized. Local markets cannot be destroyed as a result of globalization. Tariff and non-tariff barriers to intra-African trade between net food exporters and importers should also be considered by legislators. The agreement establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area lays a solid foundation for such an intervention. To smooth price and demand spikes, national and regional food reserve schemes linked to credit and insurance systems should be established and strengthened.

Innovation throughout the food supply chain should be strongly encouraged and rewarded. Africa is home to a plethora of start-ups that are at the forefront of developing climate-resilient crops, high-yielding but sustainable agriculture and aquacultural produce, and reimagining the food supply chain. The transformative potential of start-ups and other entities that create positive disruption should be harnessed, and avenues for funding and capital should be opened to such businesses.

As part of the Jesuit Justice Ecology Network of Africa's (JENA) efforts to influence policies and promote African solutions to the food crisis problem, capacity building for vulnerable and affected persons and communities is critical for long time livelihood recovery after a food crisis.

Conclusion

In the wake of the current multidimensional catastrophe resulting from Covid-19, African governments and global relief agencies should consider diversifying food supply networks. This has been evidenced in critical sectors such as health supplies, where the Covid-19 pandemic pushed several countries to take a closer look at their pharmaceutical supply chains. In addition to these policy options, African governments should strive to establish public-private partnerships as levers for achieving their developmental plans through financing and innovation in the food systems. Engaging the private sector has proved over time to promote welfare through job creation, however, legislative frameworks should protect smallscale holders from land grabbing and other harmful impacts associated with large-scale investments. Similarly, African governments should seek bilateral and multilateral agreements to support their developmental plans in funding their flagship projects without creating an unnecessary burden on their citizens through heavy taxation and other trade policy measures that end up in market distortions. The Vegetable Basket program in China demonstrates the role of the government in building a resilient food system in coordinated response with other private organizations. Finally, with the enormous challenges facing food production and supplies in Africa, post-Covid recovery may be minimally felt and only if governments insulate their citizens against price spikes. Resolving the food price increase and associated insecurity is a matter of economic, social, and political urgency. Given Africa's precarious position, food insecurity could be the spark that ignites the tinderbox. Governments must act quickly to put a stop to it.

Links

Uganda: Parish Development Model launched

Hunger in Africa surges due to conflict, climate and food prices

Related Articles

Select Payment Method

Pay by bank transfer

If you wish to make a donation by direct bank transfer please contact Fr Paul Hamill SJ treasurer@jesuits.africa. Fr Paul will get in touch with you about the best method of transfer for you and share account details with you. Donations can be one-off gifts or of any frequency; for example, you might wish to become a regular monthly donor of small amounts; that sort of reliable income can allow for very welcome forward planning in the development of the Society’s works in Africa and Madagascar.

Often it is easier to send a donation to an office within your own country and Fr Paul can advise on how that might be done. In some countries this kind of giving can also be recognised for tax relief and the necessary receipts will be issued.