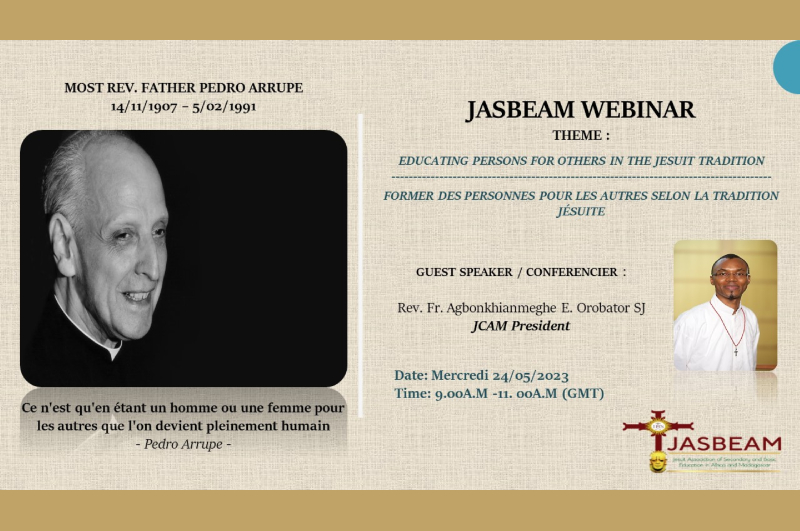

The first webinar organised by the Jesuit Association of Secondary and Basic Education in Africa and Madagascar (JASBEAM) took place on Wednesday 24 May 2023.

The theme was Educating Men and Women for Others in the Jesuit Tradition. During the webinar the guest speaker, Fr. Agbonkhianmeghe E. Orobator, SJ, the president of the Jesuit Conference of Africa and Madagascar (JCAM) in his message highlighted the following:

Preamble: the meaning of women and men for others according to Pedro Arrupe

Fifty years ago this year, Fr. Pedro Arrupe SJ spoke to Jesuit alumni in a speech titled “Men for Others, Education for Social Justice and Social Action.” To date, his speech is perhaps the best and most compelling description of the goal and objective, the meaning and purpose of Jesuit education, chief among them is the idea of educating our students to become women and men for others. Arrupe developed several themes in that insightful and prophetic speech, but for our conversation today, I would invite us to remind ourselves what it means to educate “men and women for others” in the Jesuit tradition.

According to Arrupe, the compelling criterion for evaluating the success and outcomes of our mission of education is precisely our ability to educate “men and women for others” – that is to say, people “who live not for themselves but for God and for his Christ;” “women and men who want to discern God’s will for the present times;” and who are imbued with the Ignatian spirit. Persons for others are

• practitioners of “creative love,” for “creative love does not love only what is lovable; it loves everything, and by the power of love makes it everything that is loved lovable”;

• “agents and promoters of change”;

• “docile before God” and “persons who are impelled by the Holy Spirit.”

For Arrupe, the third element is the most important: “only ‘spiritual’ persons—in the sense of men or women of God who are led by the Spirit—will in the long run be able to be persons for others, persons for justice, persons capable of contributing to a true transformation of the world that will eliminate from it the structures of sin.” In reading or rereading these criteria, we may have noticed clear echoes of the Universal Apostolic Preferences.

These points highlighted by Arrupe also provide principles for discerning concrete actions that promote the mission of education. This, in the words of Arrupe, entails “repentance and conversion” and “continuous formation.”

In the understanding of Arrupe, the ultimate goal of Jesuit education is “the creation of new persons, men and women of service” and “for others.” In other words, our students “must be men and women who are motivated by a genuine Gospel charity…” a charity that strengthens faith and kindles a desire for justice. The new person that we are called to form is, in the words of Arrupe, “the evangelical person, who looks on every other man and woman as a brother or sister.” In other words, “the ideal human being, the person who is the goal of our educational efforts” is “the spiritual or ‘pneumatic’ person, guided and sustained by the Pneuma of God, by the Holy Spirit.

Educating persons of others has significant implications for how we understand and fulfil our mission of education.

First Point: The idea of “persons for others” is rooted in the foundational Ignatian vision

If we recall, after his conversion, Ignatius desired to live as a pilgrim, surviving on alms, as he made his way in Jerusalem. His plan to live in the Holy Land failed and he was forced to repatriate to Europe. But Ignatius was not deterred: he was convinced that God wanted him to live a life of service to others. The question was where and how.

For him, in the language of his time, service to others meant to “help souls.” We find this expression “practically on every page” of the principal documents of the Society of Jesus (John O’Malley, The First Jesuits, 18). Ignatius and his companions “used it again and again to describe what motivated him and was to motivate the Society…. as the best and most succinct description of what they were trying to do” (ibid). “By ‘souls’ the Jesuits meant the whole person. Thus they could help souls in a number of ways, for instance, by providing food for the body or learning for the mind…. No doubt, however, the Jesuits primarily wanted to help the person achieve an ever better relationship with God” (18-19).

Formula of the Institute, produced by the original companions after the 1539 deliberations, identified the key ministries of this new order. Notably schools were not mentioned. Preaching and lectures related to the word of God and the education of children and unlettered persons related to Christianity or what we might today call catechism.

However, quite early on, from 1548 in Messina, Sicily, Italy, the schools became “part of the Jesuits’ self-definition” (O’Malley, 15). Helping souls is the origin of the idea of women and men for others, which is a slogan that dominates Jesuit and Ignatian mission of education. Formal education became our hallmark or brand as “the teaching order” and our chief means for helping souls. By suppression in 1773, we were operating more than 800 universities, seminaries and especially secondary schools – a development without precedent in history dedicated solely to forming the whole person.

Second Point: Educating persons for others in the Jesuit tradition implies that the pursuit of knowledge is never an end in itself

Educating persons for others is a transcendental enterprise, not in an otherworldly manner, but as a call to “something that is greater than the self, that is more encompassing than the individual's own interests” (Father Arturo Sosa SJ). Part of the purpose of Jesuit education is to help our students to reach out with passion and compassion “to the men and women of our broken but lovable world” (GC 35, 6 “Collaboration at the heart of mission,” no. 3), so that “the entire world becomes the object of our interest and concern” (GC35, d. 2 “A fire that kindles other fires,” no. 23). This means that whatever we do with our students, it must help them to discover their vocation of service of others, especially those who are impoverished, marginalized, and oppressed.

As the former Superior General Adolfo Nicolás once said, quoting his predecessor, Peter-Hans Kolvenbach SJ, “This means that we aim to bring our students beyond excellence of professional training to become well-educated ‘whole person[s] of solidarity’.” (“Depth, Universality, and Learned Ministry: Challenges to Jesuit Higher Education,” Remarks for “Networking Jesuit Higher Education: Shaping the Future for a Humane, Just, Sustainable Globe,” Mexico City – April 23, 2010).

Third Point: Educating persons for others in the Jesuit tradition is not limited to formal teaching of pedagogical content and subject matter

In the Ignatian perspective, those who serve as educators are first and foremost women and men who strive, creatively and innovatively to model the experience of God for others; people who lead others to imbibe, experience and practice the finer manifestations of the spirit, such as conscience, competence, character, compassion and commitment. To educate persons for others means becoming witnesses: in the work we do and in the people we accompany in our schools, we witness to these core values.

We speak often about conscience, competence, character, compassion and commitment as the critical, core and constitutive elements of Ignatian education. These are not values that we simply impact by the fact of formal teaching. An Ignatian educator is the person who, in speech and action, lives by these core values and principles of Ignatian education – how well they succeed in modelling these values for others can be seen in the quality of their commitment, the depth of their faith and the example of their lives.

Remember the inspiring words of Paul VI, that “People of our generation listen more willingly to witnesses than to teachers, and if they do listen to teachers, it is because they are witnesses.” (Evangelii Nuntiandi, 41).

Fourth Point: Educating persons for others in the Jesuit tradition is a project of collaboration

“Many hands are surely needed” (GC 35, 6 “Collaboration at the heart of mission,” no. 30). Collaboration and cooperation “based on discernment and oriented toward service” (GC 35, d. 6: Footnote, no. 1) are the key ingredients of our commitment and mission to women and men for others. We are partners, called to a shared mission, companions in the mission of Jesuit education. Again, as Adolfo Nicolás said, concerning this mission of Jesuit education, we know from experience that it is a mission “far greater than what any single Jesuit can dream or do; greater than what any group, community or congregation can aim at” (“Depth, Universality, and Learned Ministry”). “That is why,” he continues elsewhere, “we need a spirit of TOTAL COOPERATION with others, be they lay persons, diocesan clergy, other religious or even people from other faith traditions” (Letter in Commemoration of the 20th Anniversary of the Death of Fr. Arrupe,” 5 February 2011).

Long before Adolfo Nicolás, on September 10, 1980, in a speech titled, “Our Secondary Schools: Today and Tomorrow,” Arrupe described lay collaborators in Jesuit secondary schools as “a most important part of the educational community” and “multiplying agents.” Arrupe expressed his “profound conviction that lay people have an invaluable contribution to make in our apostolate; they help us to extend the apostolate almost without limit.” “Today,” declared Father Arrupe, “we need multipliers, and that is what our lay collaborators are.” He explained: “This means that we do not regard them as salaried employees, hired to do work under a master's supervision. They are not that!” They are “not just teachers,” but they are “responsible collaborators, who share in the fullness of our mission.” They are women and men from whom we learn (Pedro Arrupe, SJ, “Our Secondary Schools: Today and Tomorrow,” September 10, 1980). So, because of the collaborators in Ignatian education, this ministry is an apostolate “without limit,” a mission sans frontier, providing our students with new and exciting possibilities for a truly international and truly global education.

Fifth Point: Educating persons for others in the Jesuit tradition includes a wide range of “others”

When we speak of others, we do not intend extraterrestrials. Primarily we mean children, women and men who exist and survive on the margins and in the peripheries of societies – those who are marginalized, excluded and oppressed, in other words, victims of unjust socio-economic and political systems, “whose dignity has been violated….”

A few years ago, while speaking to staff and friends of the Jesuit Refugee Service in Rome, Pope Francis said: “To give a child a seat at a school is the finest gift you can give.” Millions of children across the world dream of a seat at a school. In Central African Republic, child soldiers who should be in school “have been given guns instead of pens,” according to Cardinal Dieudonné Nzapalainga of Bangui; in north eastern Nigeria, Boko Haram is “using children as suicide bombers,” most of them girls; and in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Amnesty International reports that children as young as seven are working in perilous conditions to mine cobalt that ends up in our smartphones, cars, and computers.

The late former president of Tanzania, Julius Kambarage Nyerere, once protested: “We say that man [and woman] is created in the image of God. I refuse to imagine a God who is poor, ignorant, superstitious, fearful, oppressed and wretched – which is the lot of the majority of those he created in his image.” At the heart of the Ignatian mission of educating persons for others lies a profound desire to create those conditions, opportunities and environments that will enable each student to become a full citizen of the world and attain his or her full potential in the image and likeness of God.

A few years ago, Adolfo Nicolás, declared that “Jesuit education should change us and our students…. And the meaning of change for our institutions is ‘who our students become,’ what they value, and what they do later in life and work.” One concrete manifestation of this change in our students is, he said, “the creative imagination to work toward constructing a more humane, just, sustainable, and faith-filled world.”

Educating persons for others in the Jesuit tradition entails educating for healing a “broken world, especially the world of the poor”; educating for social justice and reconciliation; educating persons to recognise and collaborate with “God … already at work in our world” to create “a new heaven and a new earth.” (Revelation 21:1). So, as Fr. Nicolás invites us to do in a contemplative consideration of our mission of Ignatian education,

Picture in your mind the thousands of graduates we send forth from our Jesuit universities [and schools] every year. How many of those who leave our institutions do so with both professional competence and the experience of having, in some way during their time with us, a depth of engagement with reality that transforms them at their deepest core? What more do we need to do to ensure that we are not simply populating the world with bright and skilled superficialities? (Adolfo Nicolás, S.J., “Depth, Universality, and Learned Ministry”).

But, also, others mean our common home. Education in the Ignatian tradition means educating people for a sustained commitment to the protection and care for this Earth, our Common Home, as a preferential, ethical and faith-directed option.

As Pope Francis says in his Encyclical Letter, Laudato Si’, this means teaching our students to value “ecological equilibrium [that strives to establish] harmony within ourselves, with others, with nature and other living creatures, and with God” (LS 210). Second, educating people to embrace “ecological citizenship” and cultivate “sound virtues” that enable people “to make a selfless ecological commitment” in their local communities (LS 211). Third, empowering people to overcome rabid consumerism and promoting “a new way of thinking about human beings, life, society and our relationship with nature” (LS 215). Finally, educating people “to see and appreciate beauty [and] … learn to reject self-interested pragmatism” (LS 215).

If we are able to educate persons for others in an ecological sense, we will convert and transform our students into stewards of environmental integrity and teach them, according to the prayer of Laudato Si’, “… to discover the worth of each thing, to be filled with awe and contemplation, to recognize that we are profoundly united with every creature as we journey towards [God’s] infinite light.”

Concluding Reflection and Prayer

I would now invite you to prayerfully recall to mind some parts of the conclusion of the inspirational address by Pedro Arrupe on the idea of women and men for others: This Spirit who makes us spiritual is also the Spirit of Christ, who makes us Christians and makes us other Christs. In this task of promoting justice, Christ is everything: our Way, our Truth, and our Life. Christ is par excellence the “man for others,” the one who goes before us in the construction of the Kingdom of Justice; Christ is our model and our obligatory point of reference.

Christ is also the foundation of that very Ignatian “magis” which moves us never to put limits on our love, but rather to say “more” and “more,” and to seek always the “greater glory of God,” which will be realized concretely in our greater commitment to human beings and the cause of justice.

Message in French {HERE}

Related Articles

Select Payment Method

Pay by bank transfer

If you wish to make a donation by direct bank transfer please contact Fr Paul Hamill SJ treasurer@jesuits.africa. Fr Paul will get in touch with you about the best method of transfer for you and share account details with you. Donations can be one-off gifts or of any frequency; for example, you might wish to become a regular monthly donor of small amounts; that sort of reliable income can allow for very welcome forward planning in the development of the Society’s works in Africa and Madagascar.

Often it is easier to send a donation to an office within your own country and Fr Paul can advise on how that might be done. In some countries this kind of giving can also be recognised for tax relief and the necessary receipts will be issued.