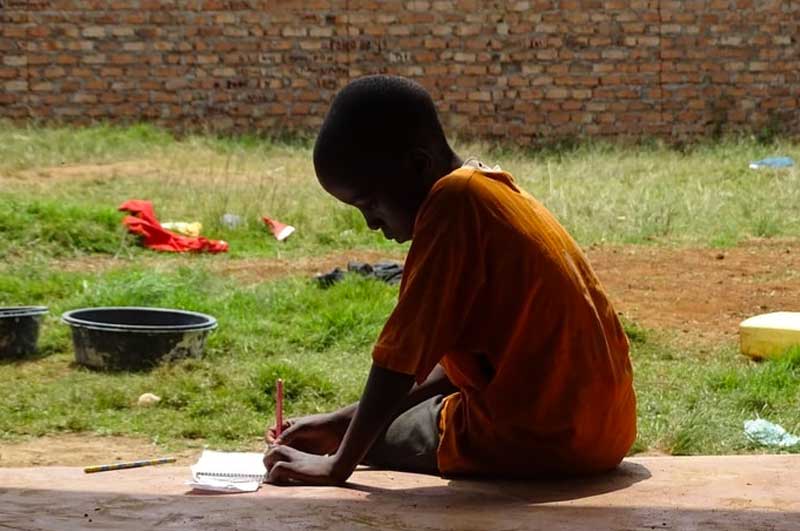

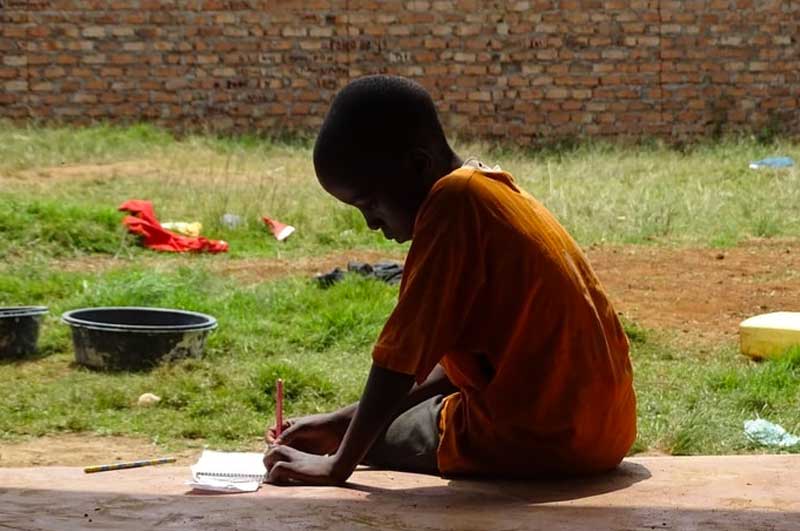

With only a few exceptions, all across Africa just like elsewhere in the world, schools have been closed in an effort to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. According to the United Nations, the world over, 166 countries closed schools and universities. UNESCO reported that the closure of schools affected 1.5 billion children and young people across the globe, representing close to 90 percent of the enrolled population. The well-intended measures to contain the spread of the virus put additional stress on education systems in Africa, which are already struggling to provide quality education for all.

While we lament the negative impacts of school closures, the coronavirus crisis has at the same time presented opportunities for reimagining education delivery. But how to do this in ways that are inclusive and ensure that no child is left out. Many countries and schools have mooted innovative pathways to beat the prolonged closure of schools. School systems turned to technology as an alternative to in-school instruction that has been impracticable; they have carried out online classes and instruction. Already, talk has emerged among many educators who are talking of “reimagining” education in ways that will shift it from a classroom- and teacher-centered model.

However, as was expected, the move has exposed the glaring digital divide and inequity as many pupils and students in Africa don’t have access to the internet, let alone cannot afford the data bundles for internet access. This divide exists even within the wealthiest countries. In the State of California for example, the fifth-biggest economy of the world, the heart of technology itself and home to the fabled Silicon Valley, only just above 50 percent of low-income households have broadband subscriptions. The internet inclusive index shows that African countries rank in the bottom third of countries in terms of internet availability and affordability. Clearly, online classes and instruction are not an option for most African children and this presents a serious justice issue that needs serious and quick attention.

Appropriate Technology

Internet-based ways of reimagining the delivery of education are a great effort but under the current circumstances and given the African context have seriously exacerbated inequity. Economist Ernst Friedrich "Fritz" Schumacher in his work Small Is Beautiful proposed appropriate technology, a movement encompassing technological choice and application that is small-scale, affordable by locals, decentralized, labour intensive, energy-efficient, environmentally sound and locally autonomous. Like Schumacher, many modern-day proponents of appropriate technology also emphasize that technology should be people-centered. Most countries in Africa have a simpler radio and television infrastructure, like community radio and TV stations, which schools, communities, and governments might consider rather than rushing into potentially expensive new education technology investments, which would only exclude countless learners and exacerbate inequity. Why can’t African governments and school systems consider rapidly scaling up educational radio and television programming, through community radios, which has the potential to reach a great number of students and educators?

Here are some considerations on how to make this happen

Forming new partnerships in education delivery. The coronavirus conundrum is one that cannot be solved by governments alone. The challenge to keep children learning during the pandemic has opened up myriad pathways to ensuring continued education delivery. In Africa, religious groups and development organisations own community radio stations that could provide the necessary infrastructure for reaching even children in far-flung areas in most affordable ways. New partnerships can be formed to bring solutions to the table from community radio stations, religious organisations, NGOs, parents and teachers.

Let everyone in. Out of the current crisis, an opportunity has emerged for us to seriously reflect on how we can bring more children into education systems especially those who were not in school before the pandemic. Our special focus should be on those with disabilities or living in extreme poverty and those that have not been reached by remote learning during the school closures.

Many, especially girls have dropped out; they need to be brought back in. With the long stretch of school closures for the last few months, many children who were already in school especially girls have dropped out completely. It is just that we don’t learn from history. After the Ebola crisis, girls’ school enrolment did not return to pre-crisis levels in West Africa, for example. Already there are reports indicating an emerging shadow pandemic of children dropping out of school and never returning. Since the beginning of the lockdown, there have been an alarming number of stories of girls being sent early to their marital homes and straight into domestic servitude and sexual abuse. For such kids, the likelihood of reentering school is next to nil. Experts worry the pandemic could roll back decades of progress on gender equality and girls’ education.

We need to be concerned and empathetic to the vulnerable and ensure they too have a future. We need to pay particular attention to most vulnerable and marginalized children like girls, poor children, orphans, refugees, etc. and bring them back into school systems. We need to make great effort and reach out to these children with specific strategies to incentivize enrolment, such as fee waivers for the poorest, adjusted enrolment requirements, and physically reach out in a targeted and caring way to children, families, and communities.

Fr. Charlie B. Chilufya SJ, is the Director of the Justice and Ecology Office of the Jesuit Conference of Africa and Madagascar (JCAM)

Related Articles

Select Payment Method

Pay by bank transfer

If you wish to make a donation by direct bank transfer please contact Fr Paul Hamill SJ treasurer@jesuits.africa. Fr Paul will get in touch with you about the best method of transfer for you and share account details with you. Donations can be one-off gifts or of any frequency; for example, you might wish to become a regular monthly donor of small amounts; that sort of reliable income can allow for very welcome forward planning in the development of the Society’s works in Africa and Madagascar.

Often it is easier to send a donation to an office within your own country and Fr Paul can advise on how that might be done. In some countries this kind of giving can also be recognised for tax relief and the necessary receipts will be issued.