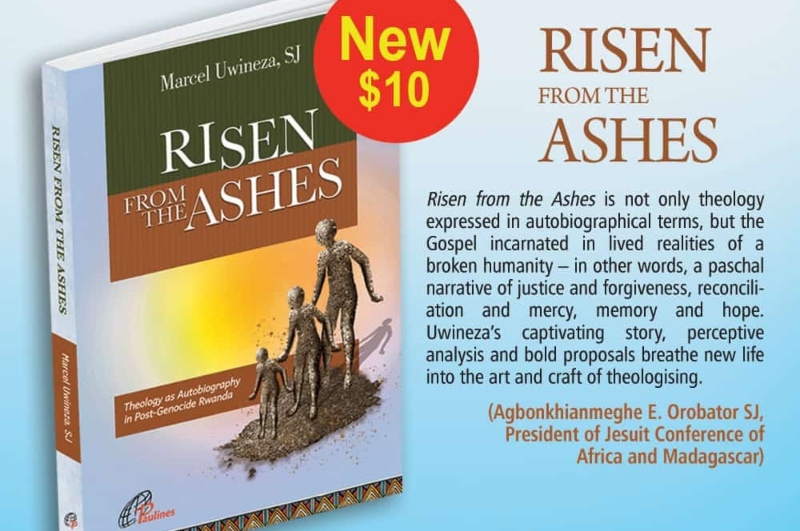

I just finished reading the recent book of Father Marcel Uwineza, s.j. “Risen from the Ashes” published by the Paulines Publication, Nairobi 2022. It is an original way of writing theology as an autobiography, something that is also at the origin of the Society of Jesus, the Jesuits. Saint Ignatius of Loyola is known especially because of his Spiritual Exercises but, for the first Jesuit companions, the Autobiography dictated by Ignatius to Father Gonsalves da Camara is also a foundational document and not just a chronicle of his life. One among those first Companions, Father Jerome Nadal, was reported to have said that “the Father [ Ignatius] could do nothing of greater benefit for the Society of Jesus than this, and that this was truly to found the Society.”

This shows to what extent an Autobiography can become a vehicle of such great theological, historical, and spiritual value. The book of Father Uwineza, therefore, is not a novel but a real work of narrative theology, as late and beloved professor Laurenti Magesa explains in the Preface, perhaps the last writing of his life. This gives the tune in which the reader must approach the reading of the entire book.

The book is well organized. Moving from personal childhood memories (Chapter I) the author gives the historical context before the Genocide of 1994 (Chapter II). Then, from the dramatic survival during the genocide (Chapter III) to the spiritual and theological reflection on Forgiveness and Hope (Chapter IV), on the Theological Formation of Priests (Chapter V), and the identity of a Priest (Chapter VI). Chapter VII resumes the proper autobiographic style of the “new life” of Father Uwineza in the United States in which he relates some main events of his priestly ministry (Chapter VII) among which his speech at the United Nations meeting in New York and the International Conference in Rwanda are described in detail. A special chapter is consecrated to his “New Parents”, the couple of John and Anne Maloy, an experience that has marked his life until the present day (Chapter VIII).

The final chapter (Chapter IX and the Epilogue) is oriented to the future and is focused on the Vocation of a Theologian in Post-Genocide Rwanda. It is said that Saint Anselm conceived Theology as having two eyes: (“ante et retro oculata est theologia”) one in front to see the present and the future and one behind to keep an eye for the past, which, in the case of Father Uwineza, is an eye towards the iconic Nyamata church. I must confess that among all the books and comments that I have read about the Genocide against the Tutsi, the narrative remains mostly focused on the past as a horrible and unhuman disgrace but few of them have the courage and the creativity to ask the question spontaneously asked by the converted Paul: “What must I do?” (Cf. Acts 22:20).

For Father Uwineza there is a clear conviction that Rwanda, called in the past “the star of evangelization in Africa”, needs to be evangelized anew and differently. The author makes his the words of the African Theologian Emmanuel Katongole: “Christianity made little difference in Rwanda. Christianity seemed little more than an add-on, an inconsequential relish that did not radically affect people’s so-called natural identities nor the goals or purposes they pursued…This failure calls for a transformation of mind…Christianity is meant to shape a new identity within us by creating a new sense of “we” – a new community that defies our usual categories of anthropology.”

A transformation of minds implies the evangelization of the entire culture of a people, an agenda that may seem “mission impossible” for many. However, such is the main agenda, not only for Rwanda but for all cultures in our contemporary society. There is not a given “Christian culture” or “Christian civilization” when, following the teaching of Pope St. Paul VI, even the holy Catholic Church must be continuously purified and continuously evangelized: “The Church is an evangelizer, but she begins by being evangelized herself. She is the community of believers, the community of hope lived and communicated, the community of brotherly love, and she needs to listen unceasingly to what she must believe, to her reasons for hoping, to the new commandment of love”.

This agenda has been more recently reassumed and confirmed by Pope Francis with a programmatic statement that summarizes the whole mission of the Church today, valid for all peoples: “It is imperative to evangelize cultures in order to inculturate the Gospel”.

Allow me at this point, to recall my memories of a Vatican press conference that I attended during the first African Synod, exactly while the Genocide was boiling in Rwanda. The late Cardinal Laurent Monsengwo, then Bishop of Kisangani, was reported to have said in the Aula of the Synod, reacting to the sad news on the genocide in Rwanda: We in Africa have a Swahili proverb that is well known: “Damu ni mzito kuliko maji” (Blood is heavier than water). But he added: “even it is the water of baptism.”

The proposal of Father Uwineza, therefore, rejoins the “signs of the times” for the life and mission of the Catholic Church today. A mission that is not the responsibility of the ecclesiastical hierarchy only but of the whole Christian community in which the theologian has a particular responsibility as he stresses at the end of his book: “Theologians have the responsibility of critique whenever the Church attempts to evade the dangerous memory of the crucified Jesus either by slipping into a “fatal banality” or embracing conformity so passive that the Church drifts from the resolute work of justice and, thereby, betrays the transcendent mystery of the relation between God and God’s people through ecclesia in Africa”.

I have heard voices, even from the Rwandan clergy, that triumphally consider that Rwanda is now and forever reconciled. Far from declaring the genocide a human (or rather inhuman!) disaster belonging to the past, Father Uwineza challenges this attitude: “Indeed. the 1994 genocide and its aftermath have raised questions that challenge the very essence of the meaning of the Church, theology in its multiple dimensions, the missionary enterprise, the mission of the Church and the place of human dignity in our faith.” If this challenge is heartily accepted by many of the members of the People of God in Rwanda, this book would have reached its purpose.

Rodrigo Mejía Saldarriaga, SJ is, the Titular Bishop of Vulturia, and Apostolic Vicar Emeritus of Soddo - Ethiopia.

Download the PDF of the book review {HERE}Related Articles

Select Payment Method

Pay by bank transfer

If you wish to make a donation by direct bank transfer please contact Fr Paul Hamill SJ treasurer@jesuits.africa. Fr Paul will get in touch with you about the best method of transfer for you and share account details with you. Donations can be one-off gifts or of any frequency; for example, you might wish to become a regular monthly donor of small amounts; that sort of reliable income can allow for very welcome forward planning in the development of the Society’s works in Africa and Madagascar.

Often it is easier to send a donation to an office within your own country and Fr Paul can advise on how that might be done. In some countries this kind of giving can also be recognised for tax relief and the necessary receipts will be issued.