The sound is crackling. The image is blurry. People join and are disconnected almost randomly. Reassuringly at least, a mosaic of two-dimensional images of people waving and smiling gradually populates our computers and mobile phones as all the invitees of our planned online call start to join.

The challenge we have connecting is about more than just digital technology, however, this is an experiment in human connection, too. Most people have no knowledge of who the others are on the other side of the screen, how we are going to communicate in the diverse languages we speak, or how valuable their own contributions will be. But everyone seems to trust the process. Our faces shine with an inspiring eagerness to listen and start a dialogue. And so it happens.

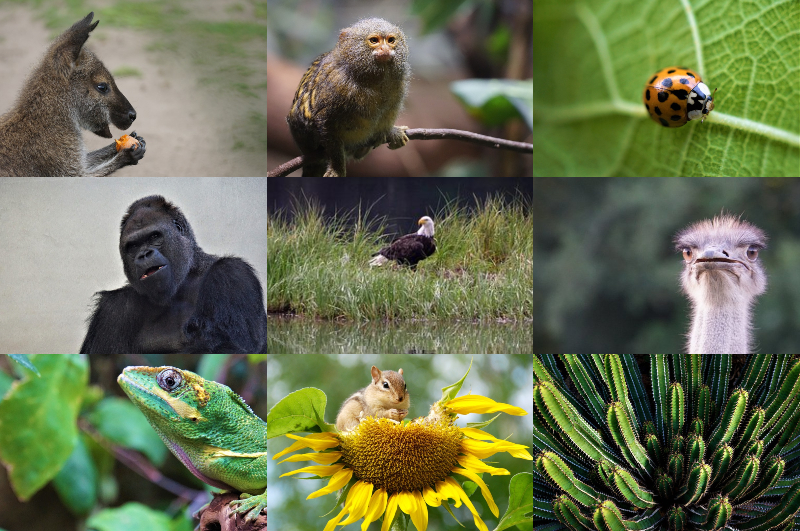

When our conversations come to a close after three intense days, we all breathe a sigh of relief. In these early, tentative steps, all we wanted was to sow seeds of dialogue among diverse communities of people from Africa and Europe that would not have otherwise connected. We defied all sorts of barriers. The first one, the most important, was perhaps the most daunting. We all gathered to share our ideas and experiences about the challenges we are currently facing in restoring ecosystems in holistic and sustainable ways. We shared about our efforts to advance the restoration of ecosystems with a more “integral” way of looking at our relationships with nature, with others, and with our values, ethics, morals and faith. It’s no accident we chose to talk about “integral ecosystem restoration” as a new angle of approaching broken ecosystems. We find inspiration in Pope Francis’ idea that ecological and social challenges need to be addressed simultaneously as part of an “integral ecology.”

The second challenge is no less daunting. We all speak different languages and come from a wide range of cultural, economic, and social backgrounds. Some of us are from Europe or North America, but the great majority come from six countries in Africa: South Sudan, Malawi, Kenya, Madagascar, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Zambia. In addition to English, we speak Dinka, Mabanese, Kiswahili, Malagasy, Bemba, Nyanja, Lingala, Chichewa, and French. It’s not an easy feat to say the least. Friendly translators from each of these languages scratch their heads and have a hard time figuring out what we are talking about, never mind translating it. And yet, somehow as we warm up in the spirit of encounter, solidarity, and conversation, our words start to spread and cross-pollinate across the airwaves with increasing clarity. We all sense that it is a unique privilege to be gathered around this online global campfire lit by ideas based on practice, by each others’ experiences in healing and bringing ecosystems back to life and health. These ideas, like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, start making sense only when we collectively discern how they fit together under the light of our values.

Why should we care about healing the ecosystems that surround us? What values drive our actions, policies, and practices shaping ecosystem restoration initiatives in contemporary Africa? Do these values conflict with each other, or do they reinforce a certain vision of our relationship with the natural world? Such were the first questions that ignited our dialogue. After all, humanity has managed to “forget” that its well-being depends on maintaining the fragile health of the planet. No ecosystem can resist the relentless deforestation caused by industrial farms that eat up and exhaust ever more land. No ecosystem can stand the advance of climate change extremes where too much or too little water or heat becomes the norm. And so the story goes.

Those of us from Europe are researchers humbled by the fact that we are in the presence of community representatives and hands-on experts from Africa. We hear how Malawi suffers from significant deforestation, but traditional religious and faith-based values have maintained and protected fragments of the original landscape. It is not permissible to cut down trees in cemeteries or traditional gathering places because the sacred bond between the dead and the living would be broken. Deforestation itself is frequently driven by charcoal production, which is an informal way to engage in the cash economy and often the only cooking fuel available to poor families. The urgent need to survive clashes with the long-term need to practice sustainable ways of life. Sand miners in Kasungu and Lilongwe, also in Malawi, experience a similar conflict: they know that mining pollutes water that is already scarce in the dry season. This clashes with their desire to practice healthier and more sustainable practices. The problem is that they feel trapped by the economic model in which they live. They mine to survive.

The values that move people to care about the ecosystems around them differ greatly. In our dialogues, some communities valued access to things easily measured in utilitarian and human-centered, “anthropocentric” ways. These communities care for nature because it provides access to water, a basic income, food, or physical security. They emphasize the importance of nature as a guarantor for the flourishing of human lives and their livelihoods.

In contrast, other communities focus on dimensions that do not easily fit utilitarian or human-centered perspectives. They focus on values, beliefs, and ethical dimensions that are harder to measure, but key to re-balancing and healing ecosystems. For instance, some communities valued access to beautiful natural environments as a legacy for present and future generations.

Communities like those from Maban, South Sudan, talked about ecosystem decline and biodiversity loss with a sense of tragedy, not just for aesthetic reasons, but because of the irretrievable losses to their cultures, traditions, and history. Other communities advanced the idea that restoring ecosystems is more about transferring and modifying educational and cultural values that need to be passed on and shared to younger generations. They highlighted, for instance, how the government’s active role in policy making is key to protect ecosystems, but this contrasts with what many governments actually do in their pursuit to extract profits from nature.

In trying to capture and understand what makes African communities “move and be moved” to restore their ecosystems in more integral ways, we found a landscape of conflicting ideas and tensions. It seems that the idea of an “integral ecosystem restoration” is rooted at the heart of these complex local realities, but its practice is plagued with challenges. It was easier to spot how non-integrality is dominant in the current ways of valuing nature. The lack of integral approaches to nature is harmful for all of us. What is exciting is discovering that these reflections only touch the surface of a much larger body of wisdom and knowledge. Our work has only just begun.

Related Articles

Select Payment Method

Pay by bank transfer

If you wish to make a donation by direct bank transfer please contact Fr Paul Hamill SJ treasurer@jesuits.africa. Fr Paul will get in touch with you about the best method of transfer for you and share account details with you. Donations can be one-off gifts or of any frequency; for example, you might wish to become a regular monthly donor of small amounts; that sort of reliable income can allow for very welcome forward planning in the development of the Society’s works in Africa and Madagascar.

Often it is easier to send a donation to an office within your own country and Fr Paul can advise on how that might be done. In some countries this kind of giving can also be recognised for tax relief and the necessary receipts will be issued.